A trustee is responsible for managing a trust—a legal arrangement that places specific assets under the trustee’s control and ownership. While they often play a crucial role in estate planning and distributing assets, trustees can also manage other matters, such as charitable trusts or bankruptcy cases. Below, we’ll discuss a trustee’s core responsibilities and how to select the right one to protect your estate.

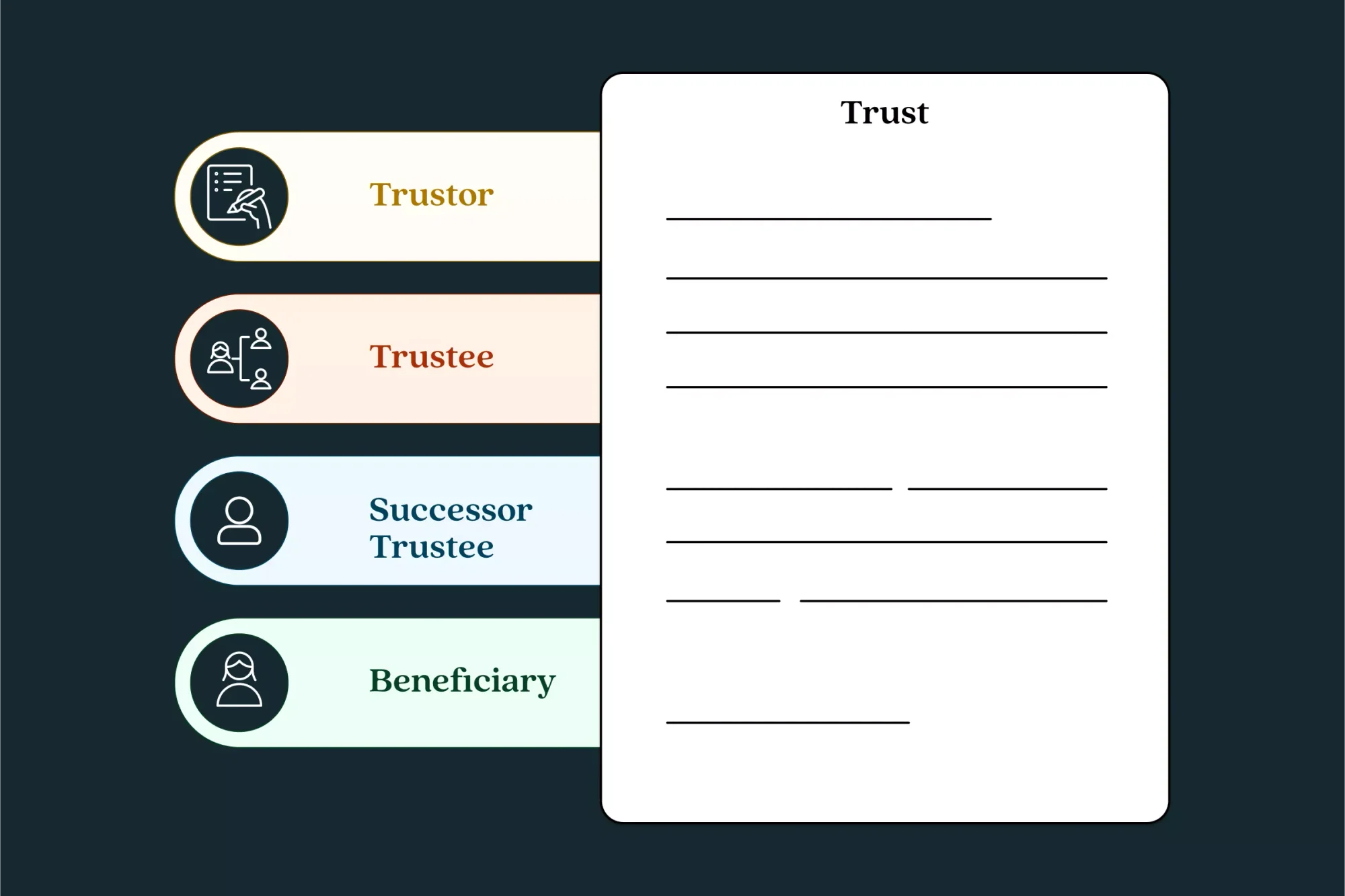

Definition: What is a trust?

A trust is a legal arrangement in which one party, known as the "trustor," transfers assets to another party, the "trustee," to hold and manage for the benefit of a third party, the "beneficiaries." This arrangement creates a fiduciary relationship, meaning the trustee has a legal and ethical duty to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries. Trusts are powerful tools for estate planning, wealth management, and achieving various financial and personal objectives.

What are the different components of a trust?

Here are the main components used in a trust:

- Trustor. The trust creator who creates and funds it with assets. Also known as the grantor or settlor.

- Trustee. The individual or institution (e.g., a bank or trust company) appointed to hold legal title to the trust assets, manage them, and distribute them according to the terms of the trust document.

- Successor trustee. The individual or institution named in a trust to manage and distribute trust assets according to the trustor’s wishes when the initial trustee dies, becomes incapacitated, or resigns.

- Beneficiaries. The individual(s) or entities who are entitled to receive the benefits from the trust assets. Based on the trust document's terms, a beneficiary can receive money from the trust, either from the interest it earns (income), the original amount invested (principal), or both.

- Trust document. The legal document created by the trustor that outlines the terms, conditions, and rules governing the trust. This document outlines the management, distribution, and conditions under which assets are to be managed.

Definition: What is a trustee?

A trustee definition in government is a person or entity (like a bank or company) who manages property or assets on behalf of beneficiaries. Although the trustee is the legal owner of the trust assets, they’re obligated to act in the best interests of those they represent. Here are a few examples of what a trustee oversees:

- Family trusts. Managing wealth and assets for future generations

- Bankruptcy. Overseeing the liquidation and distribution of assets to creditors

- Retirement plans. Managing pension funds or 401(k) plans for employees.

But, is the trustee the owner of the trust? No, the person who creates the trust (known as the grantor) is the owner of the trust and specifies who they want to serve as trustee. Sometimes, the appointed successor trustee steps into the role of a trustee of the trust when the grantor dies or becomes incapacitated.

But this isn’t always the case. Courts may need to appoint a trustee if the trust document doesn’t name one (or if the named trustee is unable to serve), as well as for matters like bankruptcy.

What does a trustee do? What are the duties and responsibilities of a trustee?

All trustees share similar trustee powers and responsibilities regardless of the type of trust they represent. Here are three duties of a trustee of a trust that take priority above all:

- Adhere to the trust terms. Act in accordance with the grantor’s instructions as outlined in the trust document.

- Fiduciary duty. Prioritize the best interests of the trust, avoiding conflicts of interest and placing the beneficiaries’ needs over their own.

- Act prudently. Handle the trust’s assets with caution and make calculated decisions that benefit all beneficiaries fairly.

A trustee is also responsible for the more practical aspects of managing the trust, many of which may change over time. Additionally, trustee management includes the following duties:

1. Distribution and conflict resolution

The trustee must keep and protect the trust assets and then distribute them as directed in the trust document. For example, an estate trust might direct that the assets be distributed to a beneficiary on their 21st birthday.

However, in cases of disputes, trustees may need to mediate between beneficiaries or seek legal advice to resolve conflicts. Sometimes, this might mean trustees need to make difficult decisions, such as withholding distributions or selling property, if they have discretion and believe it’s in the trust’s best interests.

2. Financial and asset management

Trustees must manage and invest assets in a way that aligns with the trust’s objectives and benefits the beneficiaries. This often involves day-to-day financial tasks similar to managing a household budget but on a larger scale, such as:

- Paying bills associated with the trust, such as insurance premiums or maintenance costs

- Settling any outstanding debts of the trust or the deceased

- Maintaining trust properties to preserve their value

- Monitoring or adjusting investments for long-term growth, depending on the trust’s goals

- Keeping accurate records of all financial transactions

For larger trusts, this may also involve more complex tasks, such as overseeing business interests or managing a diverse investment portfolio. However, the core principle remains the same—to preserve and potentially grow the trust assets for the benefit of its beneficiaries.

3. Compliance and legal duties

In addition to managing the finances, a trustee must adhere to all applicable laws and regulations. This includes complying with state and federal tax laws, maintaining separation between trust and personal assets, and submitting necessary reports as needed.

For example, if an estate trust earns income, the trustee must also file a U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts (Form 1041) with the IRS and pay any taxes due from the trust.

Depending on the size of the trust, trustees might also consult legal or tax professionals to ensure ongoing compliance. Likewise, a trustee may need to represent the trust in legal proceedings or defend their actions if challenged by beneficiaries.

4. Communication and reporting

Given their responsibilities and authority, trustees must maintain an open line of communication with beneficiaries and be prepared to answer their questions. They should proactively explain things like investment decisions, clarify distribution terms, or discuss the overall management strategy to reassure the people the trust is supposed to protect. Similarly, trustees are responsible for communicating with third parties on behalf of the trust, including financial institutions, tax authorities, real estate agents, or lawyers.

Types of trustees

Each type of trustee has potential strengths and drawbacks, depending on the complexity of the trust, the assets involved, and the needs of the grantor and beneficiaries.

1. Individual trustees

Individual trustees are usually family members, close friends, or trusted advisors appointed by the grantor to manage the trust. They typically have a close relationship with the grantor and beneficiaries, which enables them to understand the family dynamics and future intentions. Hence, they are also referred to as family trustees.

On the other hand, a family trustee may lack the financial or legal expertise to manage the trust or make prudent decisions. They also have to deal with family pressure and potential conflicts, in addition to having less time and fewer resources for themselves.

2. Professional and corporate trustees

This type of trustee comes into play when you consider a bank as trustee, or other wealth management companies, or law firms, or individual professionals such as attorneys or accountants. The primary advantage of a bank trustee or corporate trustees is their expertise and objectivity. The job of a trustee here is to handle record-keeping, reporting, and compliance.

However, their services come at a higher cost, and some beneficiaries may find these professionals less personal or accessible than individual trustees. There’s also a risk that larger institutions might not provide the level of personalized attention that some trusts require.

3. Government or public trustees

Government or statutory trustees are appointed by law or court order to manage trusts in specific circumstances. They often come into play when no suitable private trustee is available, or the law requires a neutral, government-appointed trustee, such as in bankruptcy cases.

Additionally, these trustees may be necessary for individuals who are unable to manage their own affairs, such as those with severe disabilities. In rare cases, probate courts may also need to appoint a trustee to administer an estate when there’s no will and no one close to the deceased steps forward.

4. Real estate trustees

A trustee in real estate is specifically responsible for managing real property held within a trust. This can include residential homes, commercial properties, or undeveloped land. Their duties are focused on the property itself, which can involve collecting rent, managing maintenance and repairs, ensuring proper insurance coverage, handling property taxes, and making decisions about buying or selling real estate in accordance with the trust's provisions.

An estate trustee must possess a thorough understanding of property management, real estate law, and local market conditions. This will help preserve and grow the value of the trust's real estate assets for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The trustee of an estate must also ensure that the property generates income or is utilized in a way that aligns with the trustor’s wishes and the beneficiaries' best interests.

How to select the right trustee

Deciding who can be a trustee of a trust is arguably one of the most critical decisions in life, as the person you name will eventually own and be responsible for managing your assets. The ideal trustee should possess a combination of trustworthiness, financial acumen, and the ability to act impartially. They should also have the time, willingness, and capability to handle the responsibilities asked of them. Here’s what you should consider for each option:

1. Family members or friends as a trustee

If you have a family member or close friend in mind who you think can be a trustee, ask yourself:

- Do they clearly understand your wishes, values, and intentions?

- Can they remain impartial, especially if they’re also a beneficiary?

- Do they have the necessary financial and organizational skills?

- Are they willing and able to take on this long-term responsibility?

A family member or friend can be a good choice if you’re confident in their abilities and believe they can handle potential conflicts. However, be sure to discuss the role with them and consider naming a successor trustee.

Alternatively, you can also consider naming co-trustees. They are multiple individuals or entities who are appointed to manage a trust collectively. They share the responsibilities and duties of a trustee, working together to administer the trust in accordance with its terms and in the best interest of the beneficiaries.

2. Trust company as a trustee

A trust company, whether a bank or financial advisory firm, might be the right choice if any of these conditions apply to you:

- Your trust is complex or involves substantial assets

- You want professional management and investment expertise

- You’re concerned about potential family conflicts

Trust companies can be particularly valuable for complex trusts, such as those involving international property, complicated or contingent terms, and requiring long-term investment and portfolio management. Still, their services should justify the fees and align with your vision for the trust.

3. Trust attorney as a trustee

Selecting a trust attorney as your trustee could be beneficial if you meet any of these criteria:

- Your trust involves complex legal issues

- You want someone with both legal and financial knowledge

- You’re looking for a professional who can provide personalized service, unlike an institution

- You need someone who can work through legal and family dynamics

A trust attorney offers specialized expertise and a more personalized approach than a large trust company, provided they have the availability. While lawyers are more expensive than appointing a family member, they also take significant obligations off their shoulders and reduce the likelihood of a direct conflict.

Whichever option you choose, ensure your trustee understands your wishes and has the ability to fulfill their responsibilities. Above all else, you want to select someone who will honor your intentions and protect the interests of your beneficiaries.

How to remove a trustee from a trust

The process for removing a trustee is a critical aspect of effective trust management because it ensures that the trust remains properly administered and that the interests of the beneficiaries are protected. A trustee can be removed through various mechanisms, each with its specific grounds and procedural requirements. Understanding these methods is crucial for anyone involved in a trust, whether as a trustor, beneficiary, or even a potential trustee, to achieve smooth trustee management.

Here are some common reasons and methods for removal:

1. Due to rejection of the role

Sometimes, an individual or entity named as a trustee in a trust document may decline the role and not accept the appointment. This can occur for various reasons, such as a lack of time, an unwillingness to assume the fiduciary responsibilities, or a conflict of interest. When a named trustee formally rejects the role before accepting it, the trust typically has provisions for appointing a successor trustee, allowing for a smooth transition. This situation is generally straightforward and avoids the legal and procedural complexities involved in removing an active trustee, who would need to be formally divested of their duties, often through resignation or a legal process.

2. Due to breaches of fiduciary duty

Trustees are legally obligated to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries and to manage the trust's assets prudently and in accordance with the terms of the trust document and applicable law. If a trustee fails to fulfill these duties, acts improperly, or mismanages assets, they can be removed. Some of the common breaches include:

- Personal benefits. Using trust assets for personal gain or for purposes not authorized by the trust, such as using trust money for personal expenses, selling trust assets to themselves at a discount, or making unauthorized withdrawals.

- Negligence. Failing to exercise reasonable care and skill in managing trust assets, leading to financial loss.

- Failure to account. Not providing regular and accurate accounting of trust income and expenses to beneficiaries.

- Conflict of interest. Placing personal interests ahead of their duty to act solely in the best interests of the trust and its beneficiaries. This might exist even if the trustee does not actually benefit, but the potential for divided loyalty is present.

- Failure to distribute income or principal. Improperly withholding distributions to beneficiaries as stipulated by the trust.

In such cases, removal often involves a court order based on a petition filed by beneficiaries, co-trustees, or other parties with a stake in the trust. The court will typically require evidence of the alleged breach and may hold hearings to determine the validity of the claims. If a breach is proven, the court has the authority to remove the trustee and appoint a successor trustee.

3. Due to the trustee’s incapacity

If a trustee becomes mentally or physically unable to perform their duties effectively, they can be removed. This ensures that the trust continues to be managed competently. The definition of "incapacity" is often outlined in the trust document itself, which may require certification from a doctor or a court determination.

For example, a trust might state that if a trustee is diagnosed with an illness or impairment that prevents them from taking proper financial decisions, they can be removed. In the absence of specific trust provisions, a court can determine incapacity based on presented evidence and prioritize the continuation of trust administration.

4. Due to the trust document terms

The trustor has significant power to shape the terms of the trust, including provisions for removing the trustee. The trust document itself can include specific clauses detailing how and when a trustee can be removed. This is a better alternative to removing a trustee and avoids court intervention. Here are some examples of such provisions:

- The majority vote of beneficiaries. The trust might stipulate that a majority vote of the adult beneficiaries can remove a trustee.

- Designated trust protector. The trustor can name a trust protector—an individual or entity appointed in the trust document by the trustor to oversee the actions of the trustee and ensure the trust is managed according to the trustor’s intentions. The trust protector (such as an attorney, financial advisor, or trusted family friend) holds specific powers, including advising, directing, or restraining the trustees, as well as the authority to remove and appoint trustees. This role is increasingly common in modern trust planning, providing an efficient mechanism for trustee changes without court involvement.

- Specific performance milestones or conditions. The trustor could set conditions for removal, such as failure to meet certain investment performance benchmarks or a change in a trustee's residency.

- Unanimity among co-trustees. If there are multiple trustees, the trust might require a unanimous decision among them to remove one of their own. For example, if a trust has three trustees—A, B, and C—then A and B can provide a unanimous vote to remove C as a trustee.

5. Due to state-specific rules

Each U.S. state has its own laws governing trusts and the removal of trustees. These laws outline the specific grounds for removal and the legal framework within which such actions must be taken. For instance, some states may have specific provisions outlining a material breach of trust, or they may establish a clear hierarchy of who can petition for the removal of the trustee.

Here are a few state-wise trustee removal rules:

- Virginia. Virginia State law § 64.2-759 permits the settlor, a co-trustee, a beneficiary, or the attorney general (in the case of charitable trusts) to seek judicial removal of a trustee. The court may grant removal for reasons such as a serious breach of trust, persistent discord among co-trustees that disrupts the administration of the trust, or if the trustee is unfit or unwilling to serve. Additionally, if all qualified beneficiaries request removal and a suitable successor is available, the court can act, provided the trust’s purpose remains intact.

- Oregon. In Oregon, a settlor, co-trustee, or beneficiary can petition the court to remove a trustee under ORS 130.625. Grounds for removal include significant misconduct, ongoing conflicts between co-trustees that hinder administration, or a trustee’s inability or refusal to fulfill their duties. The court also has the authority to initiate removal proceedings on its own if necessary, ensuring that the trust is managed in the best interests of the beneficiaries.

- District of Columbia. The District’s law (D.C. Code § 19-1307.06) authorizes the settlor, co-trustees, or beneficiaries to file for a trustee’s removal. The court may remove a trustee for serious breaches, administrative deadlock among co-trustees, or if the trustee is unsuitable or unwilling to act. Notably, a trustee can be removed by court order, even if they are not at fault, provided that all qualified beneficiaries agree and a suitable replacement for a new trustee is found. This action is permissible as long as the core purpose of the trust remains intact.

These state laws are designed to ensure that the process is legally binding and protects all parties. Consulting with an attorney specializing in state-specific trust law is crucial for understanding the precise legal procedures.

These provisions are powerful tools for the trustor to maintain control and ensure the trust's ongoing administration, even after their death.

Trustee compensation

How much does a trustee get paid?

A trustee is entitled to reasonable compensation as specified in the trust document or as determined by state law, whether that’s an hourly rate, a flat fee, or a percentage of the trust assets.

Here are some of the methods used to calculate trustee compensation:

- Hourly rate. For trusts that require intermittent management or specific tasks, a trustee might charge an hourly rate. This method is common when the trustee is an attorney, accountant, or other professional who typically bills by the hour. The hourly rate should be reasonable and reflect the complexity of the work performed.

- Percentage of trust assets. This is one of the most common compensation methods, especially for larger trusts. The trustee receives an annual percentage of the trust's principal assets. This percentage can range from a fraction of a percent to over 1% depending on the size of the trust; typically, the percentage decreases as the trust value increases (a tiered fee structure). For example, a trustee might charge 1% on the first $1 million, 0.75% on the next $2 million, and 0.5% on assets above $3 million. This method incentivizes the trustee to manage the assets prudently, thereby maintaining or growing the trust's value.

- Fixed fee. In some instances, particularly for straightforward trusts with a defined duration or specific, limited duties, a trustee might agree to a fixed fee for their services. This is less common for long-term, complex trusts, but can be suitable for trusts designed to perform a singular action, such as distributing assets upon a specific event.

- Distribution fees/Termination fees. Some trusts may allow for an additional fee when trust assets are distributed to beneficiaries or when the trust is terminated. This compensates the trustee for the administrative work involved in winding up the trust.

- Hybrid approaches. It is also possible for trustees to be compensated through a combination of these methods, depending on the specific terms of the trust and the nature of their duties. For example, a trustee might receive a base annual percentage fee, plus an hourly rate for extraordinary services or litigation.

What are the factors that influence trustee compensation?

The compensation a trustee receives can vary significantly and is generally determined by several factors, including the complexity of the trust, the amount of time and effort required, the trustee's experience, and the geographic location of the trust.

Here are some of the factors that influence trustee compensation:

- Trust document stipulations. The trust agreement itself is the primary source for determining trustee compensation. A well-drafted trust will clearly outline how the trustee is to be paid, whether it's a specific amount, a percentage, or a method for calculating reasonable fees.

- State law. If the trust document doesn't specify compensation, state laws will govern what constitutes "reasonable" compensation. Many states have statutes or common law principles that guide courts in determining appropriate trustee fees.

- Complexity of trust administration. Trusts that involve complex investments, difficult beneficiaries, ongoing real estate management, business interests, or require frequent decision-making or litigation will generally warrant higher compensation.

- Time and effort expended. The actual hours spent by the trustee on administrative tasks, investment management, tax preparation, communication with beneficiaries, and legal consultations directly impact the rationality of their fees.

- Trustee's expertise and experience. Professional trustees (e.g., trust companies, banks, experienced fiduciaries) often charge higher fees than individual, non-professional trustees, as they bring specialized knowledge, resources, and often, higher levels of insurance and bonding.

- Size and value of trust assets. Larger trusts with more substantial assets generally result in higher compensation when a percentage-based fee structure is used.

- Performance of investment duties. While not always directly tied to compensation, a trustee's success in growing or preserving trust assets can implicitly support the reason for their fees.

- Court review and approval. In some jurisdictions or in the event of a dispute among beneficiaries, a trustee's compensation may require approval by a probate court to decide if the fee is fair based on certain factors.

Keeping detailed records of their time, expenses, and actions to justify their compensation is crucial for a trustee, especially when their fees are subject to scrutiny by beneficiaries or a court of law.

Tax obligations for a trustee

Here are some of the duties that a trustee should perform in order to comply with the tax obligations:

- Obtain a taxpayer identification number (TIN) for the trust if it is considered a legal entity. For revocable trusts, the trustor’s social security number (SSN) is often used while the grantor is alive. For irrevocable trusts or after the trustor’s death, an employer identification number (EIN) is required.

- Distribute the income and principal in accordance with the terms of the trust document to the beneficiaries.

- Pay any taxes due from the trust's income and maintain accurate records of all transactions.

- Check if the trust’s annual income meets the thresholds and filing tax return (Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts).

- Ensure proper tax reporting for beneficiaries by preparing a separate Schedule K-1 for each beneficiary who received a distribution, providing each beneficiary with their copy, and attaching all Schedule K-1s to the trust’s Form 1041 when filing with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

- Understand the tax implications of trust activities, including asset sales and investments. For example, when a trust sells an asset, such as real estate or securities, it may trigger capital gains tax on any profit realized from the sale. Additionally, investments made by the trust can generate income, such as interest, dividends, or rent, which is also subject to taxation.

- Report income received for trustee services as ordinary income to the IRS, on the trustee’s personal tax returns, since it is considered taxable income.

It's advised for trustees to consult with a tax professional to ensure proper reporting and compliance with all applicable tax laws.

Legal considerations for a trustee

Serving as a trustee involves navigating a complex landscape of legal obligations and potential challenges. Understanding these legal considerations is crucial for any trustee to effectively manage the trust, protect its assets, and fulfill their duties without incurring personal liability. This section outlines key legal aspects trustees must be aware of, including liability protection, dispute resolution, and compliance with state-specific laws.

1. Liability protection

Trustees are fiduciaries, meaning they have a legal and ethical duty to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries. If a trustee breaches this duty through negligence, mismanagement, or fraud, they can be held personally liable for any losses incurred by the trust. This liability can extend to their personal assets, not just those of the trust. However, trust documents often include provisions for liability protection, such as indemnification clauses, which can shield a trustee from personal liability as long as they act in good faith and within the scope of their duties.

For further protection, trustees may consider obtaining trustee liability insurance (also known as errors & omissions [E&O] Insurance)—a type of insurance policy that protects trustees from personal financial loss if they are sued for alleged negligence, errors, omissions, or breaches of fiduciary duty while managing a trust. This coverage typically pays for legal defense costs, settlements, or judgments if the trustee is found liable for mistakes or mismanagement in the course of their professional duties.

2. Dispute resolution

Despite a trustee's best efforts, disputes can arise among beneficiaries or between beneficiaries and the trustee. These conflicts can stem from disagreements over asset distribution, investment strategies, or the interpretation of trust terms and conditions. Trustees must be prepared to address these disputes, which may involve mediation, negotiation, or, if necessary, litigation. The trust document may outline specific dispute resolution mechanisms; however, trustees often need to seek legal counsel to navigate complex conflicts and ensure that decisions are made in accordance with legal requirements and the trust's objectives.

3. State-specific laws

Trust law is primarily governed by state statutes, meaning the specific rules and regulations a trustee must follow can vary significantly from one state to another. These laws encompass a range of topics, including a trustee's powers and duties, reporting requirements, investment standards, and procedures for removing a trustee. Here are a few examples:

- Confidentiality. States like Delaware (12 Del. C. § 3303[d]) and Nevada (NRS 163.004) offer strong privacy protections, allowing trust documents to remain sealed or confidential for extended periods, whereas others, such as Alaska (AS 13.36.070), provide more public access to trust records.

- Tax treatment. Some states, including Alaska, South Dakota, and Texas, don’t impose a state income tax on trusts. Delaware exempts trusts with non-resident beneficiaries from income tax, which impacts decisions about the optimal location for income-generating trusts.

- Trust duration. Some states, such as Nevada (NRS 111.1031), limit trusts to 365 years, while others, like Alaska (AS 34.27.051), limit trusts to 1,000 years. But states like South Dakota (SDCL 43-5-8) permit dynasty trusts that can last for generations.

A trustee must have a thorough understanding of the laws in the state where the trust is administered. Consulting with an attorney specializing in trust law in the relevant jurisdiction is essential to ensure compliance and avoid potential legal pitfalls.

How does a trustee work? Important factors to consider before becoming a trustee

While acting as a trustee can be a rewarding experience, it is essential to understand the potential drawbacks and significant trustee duties that come with it. Before accepting this role, individuals should carefully consider the demanding nature of the position and its potential impact on their personal lives.

- Time commitment: Managing assets, investments, records, and taxes requires a significant amount of time, which may affect your availability for other personal duties and responsibilities.

- Personal liability: Trustees can be held personally responsible and liable for losses resulting from negligence, mismanagement, or fraud. This liability can extend to legal fees, potentially jeopardizing the trustee's personal assets.

- Emotional burden: The role involves mediating disputes, navigating complex family dynamics, and making difficult decisions, which can be emotionally challenging and demanding.

- Complex obligations: Trustees face challenging legal and tax compliance requirements, and mistakes in these areas can result in penalties. Hence, trustees often require professional help.

- Inadequate compensation: The trustee’s compensation may not fully reflect the time, effort, and risk involved, especially for family trustees.

What is the difference between an executor and a trustee?

Is a trustee the same as an executor? While both a trustee and an executor play crucial roles in managing assets and fulfilling the wishes of a deceased individual, their responsibilities differ significantly. Understanding these distinctions is vital for effective estate planning and administration.

1. Definition

A trustee in a trust manages and administers the assets held in a trust that are funded by the trustor.

An executor of a will administers the deceased person’s estate, distributes the assets to the beneficiaries, and pays off the deceased's debts.

2. Responsibilities

A trustor’s role begins as soon as the trust is established by the trustor, and it continues as long as the trust remains in existence (potentially for years). The trustee is bound to follow the terms of the trust document, which specifies how, when, and to whom the trustor must distribute the assets.

An executor’s role is typically short-term, as it begins when the will creator dies and ends after probate. The executor must follow the instructions specified in the will, which outlines how and to whom the assets are to be distributed by the executor.

Comparison Table: Trustee vs. Executor

The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Trustee | Executor | |

| Which is the legal document that holds the instructions? | Trust document | Will |

| When does the role become active? | Can be active during the trustor's lifetime (living trust) or after death (testamentary trust) | Becomes active only after the creator's death |

| What is the primary purpose of the role? | Manage and distribute assets held within a trust to the beneficiaries | Administer the entire estate of a deceased person according to their will |

| Who governs the role? | Governed by trust agreement and fiduciary law, often with less court supervision than probate | Governed by the will and probate law, with significant court supervision during probate |

| How long is the role active? | Can manage assets for an extended period, potentially across generations | The role typically concludes once the estate is settled and distributed |

Establish your trust with LegalZoom

LegalZoom's Will & Trust services make it easy and affordable for individuals to protect their assets and care for their loved ones. Unlike traditional estate planning, which can be complicated and expensive, LegalZoom uses technology and legal advice to simplify the process. This gives customers confidence and control over their future plans.

Here is what our customer has to say:

I'm stunned at the precision and ... quality of the end product ... There's a reason why they're No. 1…

- Teddy F., living trust customer

LegalZoom offers a range of benefits that make estate planning easier, more affordable, and tailored to your needs.

1. Accessibility and convenience

Create important estate planning documents conveniently from your home, at your own pace. LegalZoom's intuitive online platform simplifies the legal process, making it easy to get started. Furthermore, enjoy 24/7 access to your documents via secure online storage, ensuring your vital information is always accessible.

2. Affordability

LegalZoom offers a more affordable alternative to a traditional estate attorney. Our pricing is transparent, with clear package options. For additional support, personalized attorney assistance can be added for a flat fee, ensuring predictable and manageable costs.

3. Guidance and support

The service offers step-by-step guidance and helpful resources to empower you with informed decision-making. For added assurance, you have the option to have your documents reviewed by an attorney or schedule a consultation. Customer support is readily available to answer any questions you may have.

4. Customization and control

LegalZoom plans are attorney-designed and customizable to your specific needs and circumstances. This ensures your assets are distributed as you wish and grants you control over crucial healthcare decisions.

Planning ahead for the benefit of your estate

Trustees are key to the successful implementation of trusts. Because the entire management and implementation of the trust rests with the trustee, it is important to choose a trustee wisely.

Trustee selection is just one aspect of establishing a personal estate plan, which also may include creating a last will, a living will, and powers of attorney.

FAQs

1. What does ttee mean in a trust?

In a trust, the phrase “Ttee” stands for a trustee—a person or a bank who administers a trust. A trustee is in charge of the trust and its assets. They are those who manage and hold the legal title to a property on behalf of the beneficiary in a trust.

2. What is a trustee deed?

A trustee deed is a legal document used by a trustee to transfer real property out of a trust to a beneficiary or buyer, often after a foreclosure sale or as part of the trust administration process. In states that use deeds of trust for real estate loans, the trustee deed is used to convey title to the new owner after a foreclosure or to distribute trust property according to the terms of the trust.

3. Is a trustee the same legal title as a beneficiary?

No, a trustee and a beneficiary are different. A trustee manages the trust and its assets, while a beneficiary benefits from it. A trustee can also be a beneficiary, but they must act impartially and separate their responsibilities as trustees from their best interests.

4. Can a trustee remove a beneficiary from a trust?

Generally, a trustee can’t remove a beneficiary unless the trust explicitly gives them this authority. Otherwise, the terms of the trust and relevant state laws allow the addition or removal of beneficiaries, meaning only the grantor or a court can make such changes.

5. Can a trustee sell trust property without all beneficiaries approving?

Generally, a trustee can sell trust property without the explicit approval of all beneficiaries if the trust document grants them the authority to do so, or if the sale is necessary to carry out the terms of the trust, such as paying debts or distributing assets. However, trustees have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of all beneficiaries and must ensure the sale is fair and reasonable. If a trustee acts improperly or against the terms of the trust, beneficiaries may have legal recourse.

6. Does a power of attorney override a trustee?

A power of attorney does not override a trustee. A power of attorney grants an agent the authority to act on behalf of the principal, but this authority is limited to the assets the principal owns directly. A trustee, on the other hand, manages the grantor’s assets within a trust according to the trust's terms, for the benefit of the beneficiaries. Therefore, a power of attorney cannot grant an agent control over assets held in a trust, as those assets are legally owned and controlled by the trustee.

7. What is a substitute trustee?

A substitute trustee, generally referred to as a successor trustee, is an individual or entity appointed to take over the duties of an original trustee who is no longer able or willing to serve. This often occurs due to the death, resignation, incapacitation, or removal of the original trustee. The substitute trustee assumes all the responsibilities and powers outlined in the trust document, ensuring the continued administration of the trust according to the grantor's wishes and in the best interests of the beneficiaries. Their role is crucial in maintaining the continuity and effectiveness of the trust.

8. Does a co trustee own the property?

A co-trustee does not "own" the property in the traditional sense of personal ownership. Instead, they hold legal title to the property on behalf of the trust's beneficiaries. Their role is to manage and distribute the trust assets according to the terms of the trust agreement, acting in a fiduciary capacity. This means they have a legal and ethical duty to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries, rather than for their own personal gain. While they have control over the assets, this control is solely for the purpose of administering the trust, and the beneficial ownership ultimately lies with the beneficiaries.

9. Can a trustee change a trust?

Generally, a trustee cannot unilaterally change a trust. Their primary duty is to administer the trust according to its terms and the grantor's intentions. However, there are limited circumstances where changes might occur. If the trust document itself grants the trustee specific powers to amend certain provisions, they can act within those defined limits. Additionally, in some jurisdictions, with court approval, a trustee may be able to modify a trust if unforeseen circumstances render the original terms impractical or if all beneficiaries agree to the change and it serves the trust's purpose. Even in such cases, any modification must ultimately uphold the original spirit and goals of the trust.

10. How long can a trustee live in a trust property?

Generally, a trustee cannot live in a trust property indefinitely unless the trust document explicitly grants them this right or it's deemed necessary for the trust's administration (e.g., to oversee repairs). Their primary duty is to manage the property for the beneficiaries' benefit, and living there without authorization could be considered self-dealing or a breach of fiduciary duty. The duration of their stay, if permitted, would be dictated by the terms of the trust or the specific circumstances requiring their presence.

11. What happens if a trustee spends the money from a trust?

A trustee can only withdraw money from a trust if the trust document explicitly allows it, or if the withdrawal is for legitimate trust expenses, distributions to beneficiaries as outlined in the trust, or reasonable compensation to the trustee. They cannot withdraw money for personal use or for purposes not authorized by the trust, as this would constitute a breach of their fiduciary duty. All withdrawals must be in the best interest of the beneficiaries and in accordance with the trust's terms and applicable laws.

12. How long does a trustee have to settle a trust?

While there's no fixed rule, a reasonable time for settling a straightforward trust could range from six months to two years. More complex trusts, especially those involving illiquid assets, significant debts, or disputes, could take three to five years or even longer.

13. What is the 65-day rule?

Trustees must follow the distribution rules established by the trust; however, the IRS has a 65-day rule that allows a trustee to make additional distributions within the first 65 days of a new year and have them count for the prior tax year. This is sometimes necessary if there is extra income that was not distributed within the prior tax year.

14. What is a trustee in a will?

When a last will includes provisions for a testamentary trust, it names a trustee who manages the trust. This trustee in a will is responsible for managing and distributing the assets placed into that trust after the testator’s death. This responsibility may be for a longer duration, during which the trustee is expected to adhere to the trust's specific terms for the benefit of the beneficiaries.

This differs from an executor of a will, who administers the overall estate according to the will’s terms, such as settling debts and distributing assets. This is a short-term role, concluding after the probate process is complete.

15. What is an executor of a trust?

An executor of the trust is not a recognized legal term. An executor of a will is responsible for administering the estate of a deceased person and paying off their debts. The executor's duties are typically short-term, commencing when the testator dies and concluding upon completion of the probate process.

A trustee is a person or institution appointed to manage assets held in a trust and distribute them to the beneficiaries.

16. What is an IRA trustee?

An Individual Retirement Account (IRA) trustee, typically a financial institution, holds and administers an IRA, ensuring compliance with IRS regulations on contributions, distributions, and investments. They manage administrative duties, such as record-keeping and IRS reporting, hold IRA assets (including stocks, bonds, and mutual funds), and execute transactions as directed by the owner. Essentially, the trustee safeguards retirement funds, ensures adherence to legal requirements, and facilitates savings growth.

Miles Almadrones, contributed to this article.