Intellectual property rights are essential to all creators. After all, the right to reproduce or distribute works can expand your audience and turn a profit, allowing you to protect your work. But creators need to learn what can be copyrighted.

Copyright protections help avoid legal and financial issues around your work. They also ensure fair compensation for the use of your output. To help protect your works, we'll outline what copyright is, what is protected by copyright, and the basics of copyright law.

Intellectual property rights are essential to all creators. After all, the right to reproduce or distribute works can expand your audience and turn a profit, allowing you to protect your work. But creators need to learn what can be copyrighted.

Copyright protections help avoid legal and financial issues around your work. They also ensure fair compensation for the use of your output. To help protect your works, we'll outline what copyright is, what is protected by copyright, and the basics of copyright law.

What is copyright protection?

Copyright protection refers to ownership rights to use or distribute creative works. Copyright protection ensures that authors retain control over their work. You control an original work's copyright just by making it, and if the copyright is registered, a creator can take legal action if someone else uses or distributes their material.

To better understand copyright protections, we'll explain how it works, why copyright is important, and what works get protection.

How does copyright work?

Only original works of authorship get copyright protection. So only the original creator or agent may obtain the copyright. With this protection in place, someone:

- Can only use your work if they purchase the right to do so

- Cannot take someone else's work and receive copyright protection

Why copyright is important

Copyright gives creators ownership of their work while allowing public access to it. Specifically, copyright lets authors:

- Distribute their work

- Ensure they receive payment for their product

- Protect against plagiarism or theft

- Pursue legal action in the case of copyright infringement

What can you copyright?

Copyright protections apply to original creative works. Copyright most often applies to media such as books, movies, or sound recordings.

What is not protected by copyright?

Copyright protections don't protect general concepts, methods, or common knowledge. A work must also exist in a tangible form to receive copyright protection. For example, you can't copyright an improvised performance that wasn't recorded.

- Can you copyright an idea? Copyright does not protect ideas and concepts. However, you can illustrate or write your thoughts and copyright that work.

- Can you copyright a word? You cannot copyright a single word. Instead, you can trademark a term identifying a business and its products.

- Can you copyright a phrase? Similar to single words, you cannot copyright a phrase. That said, you can trademark a phrase used for commercial purposes.

- Can you copyright a name? You can't copyright a name, but you can trademark distinctive ones used in commerce.

- Can you copyright a product? You can claim the rights to some reproducible products in a tangible medium. On the other hand, formulas, design concepts, and processes may require a patent.

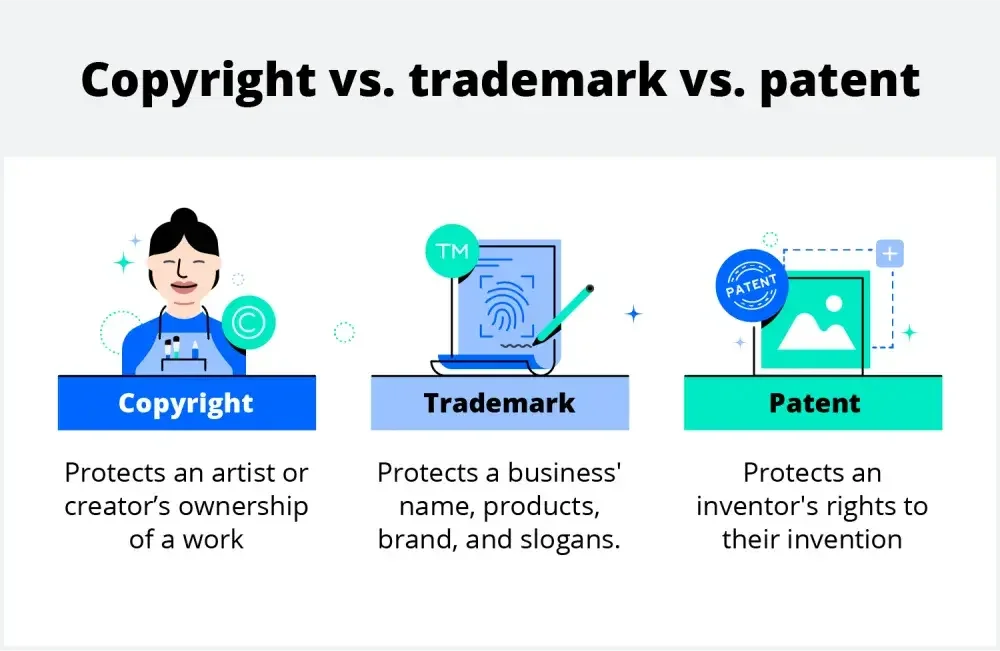

What is the difference between trademarks, copyrights, and patents?

Copyrights and trademarks protect intellectual property, but they work for different types of entities:

Copyrights:

- Give creators exclusive rights

- Protect tangible works

- Apply to media like books, movies, and music

Trademarks:

- Protect businesses from intellectual property theft

- Distinguish between brands

- Apply to words, phrases, and logos

Patents:

- Gives inventors exclusive manufacturing rights

- Protects inventions, formulas, and designs

- Apply to scientific inventions and works of engineering

12 types of works you can copyright

The following types of works receive protection under current copyright law:

Literary works

This includes novels, nonfiction works, poems, articles, essays, directories, advertising, catalogs, speeches, and computer programs. Joint writers who co-author a book each get copyright power unless they make an agreement stating otherwise.

Musical works

This category includes both musical notation and accompanying words. Copyright on the sound recording of a track falls into a different category.

Dramatic works

Dramatic works include plays, operas, scripts, screenplays, and any accompanying music. For others to put on your show, theaters or producers can pay you a licensing fee.

Pantomimes and choreographic works

This category includes dance steps and physical acting dictated by movement. Popular dance steps are not included in this type of work.

Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works

This category generally refers to visual art. The types of works in this category include:

- Sketches

- Drawings

- Cartoons

- Paintings

- Photographs

- Slides

- Greeting cards

- Architectural and engineering drawings

- Maps and globes

- Sculptures

- Jewelry

- Glassware

- Models

- Tapestries

- Fabric designs

- Wallpapers

Motion pictures and other audiovisual works

These include movies, videos, and film strips. Video content published online applies to this category. However, many platforms introduce terms of use contracts that affect your owner's rights.

Sound recordings

This includes recorded music, voice, and sound effects.

Compilations

You can assemble a collection of existing materials, and the collection can get copyright protection.

Derivative works

A derivative work is a work based on one or more already existing works, and it is copyrightable if it includes what the copyright law calls an “original work of authorship."

Works such as the "Mona Lisa" or the "Venus de Milo" are in the public domain, so anyone can use them. For example:

- Suppose someone paints a new version of the "Mona Lisa" or takes a photograph of "Venus de Milo." In that case, those works belong to the artist if they take some creativity.

- An exact photograph of the "Mona Lisa" or a replica of the "Venus de Milo" isn't protected. However, derivations that took creativity (the changes to the painting and the angle and lighting in the photograph) are protectable.

Architectural works

Previously, it was impossible to copyright a building—only the plans used to build it were copyrightable. The Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act of 1990, however, extends copyright protection to the buildings themselves. This brought the United States into compliance with the Berne Convention, a set of international rules on intellectual property.

Semiconductor chip mask works

The Semiconductor Chip Protection Act of 1984 protects semiconductor chip designs. Although the protection differs from regular copyright, the process and forms are very similar, and the Copyright Office administers the procedure.

Vessel hulls

The Vessel Hull Design Protection Act of 1998 made possible the copyrighting of the designs of boats. Protection lasts for 10 years.

Copyright law considerations

Intellectual property law plays a crucial role in copyright. To avoid legal troubles, we'll outline the main legal considerations.

What are the requirements to copyright a work?

To copyright something, it needs to display three elements:

- Originality: The work is an independent creation by the author, not a copy

- Creativity: The work relies on an author's intellect and judgment

- Fixation: The work is “fixed" into a tangible medium like a hard drive or physical pages of a book

The Copyright Act outlines technical criteria as well:

“To be copyrightable, a work of authorship must be fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which [it] can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or indirectly with the aid of a machine or device."

How do I learn if something is copyrighted?

You can find copyrights by checking work for trademarks or copyright notices. For a more exhaustive search, you can review current copyrights.

In the public catalog, you can find all copyrights registered since January 1978.

Which legal forms register copyright?

The U.S. Copyright Office uses five different forms to register a copyright. The form you file depends on the type of work you want to register. The forms focus on different types of works, including:

- Literary

- Visual

- Single series

- Performing arts

- Sound recording

What rights do copyright holders earn?

By creating a work, copyright holders receive six exclusive privileges to:

- Reproduce the work

- Distribute the work

- Create derivative works

- Publicly perform the work

- Publicly display the work

- Publicly perform sound recordings by means of digital audio transmission

Copyright best practices

To protect your intellectual property, follow these best practices:

- Register with the U.S. Copyright Office. While you don't need the office's help to register a copyright, registering allows you to enforce your copyright.

- Include a disclaimer or copyright notice in your work. A copyright notice can deter plagiarism and assert your ownership of a work.

- Include contact information. If someone wants to use your work, open yourself to contact. This will prevent future surprises and help you reach an agreement.

- Learn about permissions and fair use. Under the right conditions, you or another creator can use someone else's copyrighted work. Follow intellectual property guidelines to the letter to avoid copyright infringement.

- Consult a copyright attorney. A legal expert can help protect your intellectual property and help you get recourse after copyright infringement.

- Note the limits of copyright. You can't copyright just anything you produce. Some designs and products fall within the trademark or patent umbrella.

Copyright FAQs

To round out the last details about copyright protection and what can be copyrighted, we answered a few FAQs.

How long does copyright last?

For works created after Jan. 1, 1978, copyrights last for the entire life of the creator, plus 70 years.

What is the public domain?

The public domain encompasses all works that go without copyright protection. These works generally don't have copyrights because:

- The works were ineligible for copyright

- The copyright on these works expired

- The author never intended to copyright them

Creators can quote, borrow from, or reuse works in the public domain. For example, the copyright has expired on every original Sherlock Holmes story. So anyone can adapt or remake these works according to their own vision.

What does the © symbol mean?

Before 1989, the image of a C in a circle was a copyright notice staking a creator's claim to their work. Previously, you had to include this symbol to receive copyright protection. After 1989, the U.S. changed its copyright policy, so you only had to create a work to establish a copyright claim.

Copyright protection for any artist or brand

What does copyright protect? It protects artists' and businesses' ownership of their original works. You retain the right to reproduce and distribute your hard work by learning what can be copyrighted. Copyright protection gives you control over your output, whether you're looking to spread a message or turn a profit.